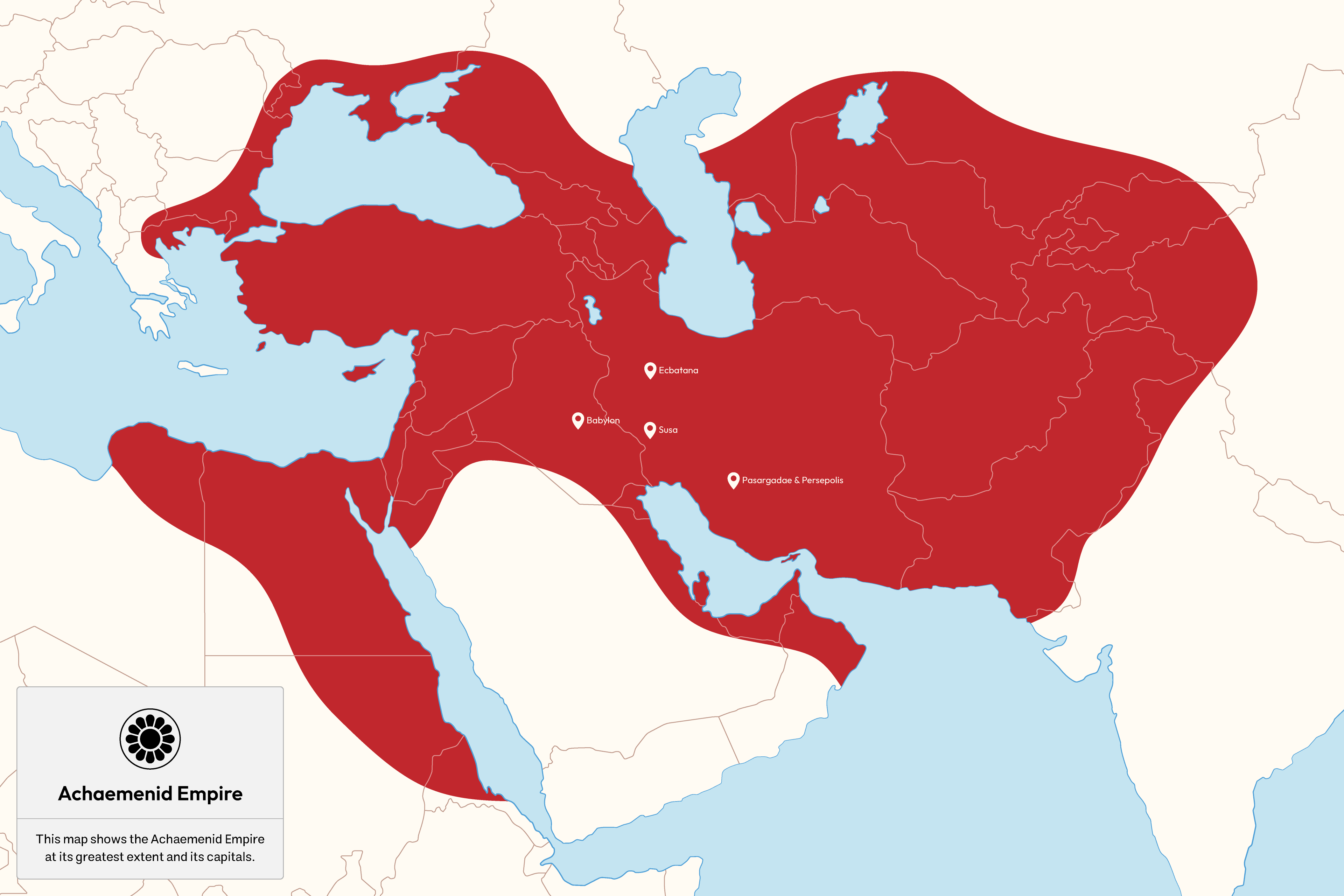

The Achaemenid Empire is recognized as the first “world order” and the earliest multi-ethnic state in history. By encompassing vast territories across three continents—Asia, Africa, and Europe—it established a new model for global governance and imperial administration. This article examines the geographical extent and borders of this empire based on historical documentation and archaeological findings.

Sources for Defining Borders

The borders of the Achaemenid Empire are determined based on three primary sources:

- Inscriptions and Administrative Tablets: These are the most reliable sources, as they originated directly from the Achaemenid power structure.

- Classical Historians: Greek writings are significant but are occasionally influenced by political bias and geographical errors.

- Archaeological Findings: Modern discoveries fill historical gaps and either confirm or refine written claims.

In this analysis, rather than relying solely on Greek texts or the Behistun Inscription (which belongs to the early years), the inscriptions of Naqsh-e Rostam are used as the primary reference. These inscriptions reflect the peak of power and the final expansion of the empire during the late reign of Darius the Great.

Stages of Expansion

Throughout Achaemenid history, several kings played decisive roles in the expansion and consolidation of the empire’s borders:

- Cyrus the Great: The founder of the Achaemenid Empire, who laid the foundations of a global empire by conquering major regional powers, including Media, Lydia, and Babylon. His campaigns in the eastern Iranian Plateau extended as far as the basins of the Oxus (Amu Darya) and Jaxartes (Syr Darya) rivers, thereby stabilizing the empire’s eastern frontiers.

- Cambyses II: Expanded the Achaemenid realm into Africa through the conquest of Egypt and Libya. Although classical sources express doubts regarding the success of his campaign against Ethiopia (Kush), the appearance of this region in later official inscriptions indicates either direct control or, at minimum, Persian political influence over these areas during this period.

- Darius the Great: Marked the phase of consolidation, administrative organization, and the apex of the empire’s territorial expansion. His campaigns reached India in the east and crossed the Danube River in the west (Eastern Europe), bringing the empire to its greatest geographical extent. According to Darius’s inscriptions, the number of provinces increased from 23 satrapies listed at Bisotun to 29 provinces recorded at Naqsh-e Rostam, reflecting the incorporation of new territories such as India and the Scythians beyond the sea.

- Xerxes I: Oversaw the final maturation of the empire’s administrative and geographical structure. In inscriptions from this period, the number of provinces rises to 30, and for the first time peoples such as the Dahae are explicitly listed among the subject lands, indicating the continued reach of Persian influence into distant regions of the empire.

Provincial Structure

At its zenith, the empire governed a vast array of civilizations under a single flag. The territory included:

- Central and Eastern Regions: Media, Elam, Parthia, Aria (Herat), Bactria, Sogdia, Chorasmia, Drangiana, Arachosia, Sattagydia, and Gandhara.

- Western and Southern Regions: Babylon, Assyria, Arabia, Egypt, Armenia, Cappadocia, Sardis (Lydia), Ionia, and Kush.

- Frontier Regions and Scythian Tribes: India, Skudra, Dahae, Maka, Caria, and various Scythian (Saka) groups.

Border Challenges

Defining precise boundaries remains difficult in certain areas:

- India: Determining the exact extent of progress into the Indus Valley requires more archaeological evidence.

- Arabia: While “Arabaya” is listed in inscriptions, the exact borders in the Arabian Peninsula are hard to define, as these areas were often joined through voluntary treaties with northern tribes rather than military conquest.

- Saka across the sea: Although Darius’s campaign into Eastern Europe is certain, the nomadic nature of the Scythians and the lack of fixed fortifications make it difficult to draw a definitive northern border line.

Modern Findings

Modern discoveries have reshaped our understanding of the empire’s scale. The discovery of an Achaemenid palace in Phanagoria (Russia) proves that the European campaigns were successful, contrary to some vague Greek accounts. Furthermore, the discovery of the Pazyryk carpet near the Mongolian border demonstrates deep Iranian cultural and economic influence in the heart of Central Asia.

Conclusion

At its peak, the Achaemenid Empire spanned from Central Asia to Eastern Europe and from India to Northeast Africa. By combining land power with a naval fleet in international waters, it created the largest political structure of its time in terms of area and population—a feat previously unprecedented in world history.